Not all business problems are obvious to everyone on the team. Agreeing on problem priority is equally troublesome. Decision management begins with people talking to each other about what’s important. It includes hopes, dreams and the current state of suffering. The conversational ‘recipe’ provided by an InRule workshop dramatically focuses attention onto actionable tasks that frame your project and express value back to the business.

What’s wrong and who is suffering?

A problem can be a story that we tell each other: ‘Our key vendor has gone out of business and now we need to pull this solution in-house.’ In other cases, problems are tales from end customers on a journey through a service function that’s not responding. Recently, I attended a claims conference in London. In the final session, nearly everyone agreed that when it comes to communicating coverage, they all struggle with balancing legally binding language against comprehension by the average customer. Building trust quickly in on-line experiences is crucial and takes experimentation. Because decision management directly impacts these journeys, we need to know the whole problem and we need a rapid framework to put these stories into something we can work with.

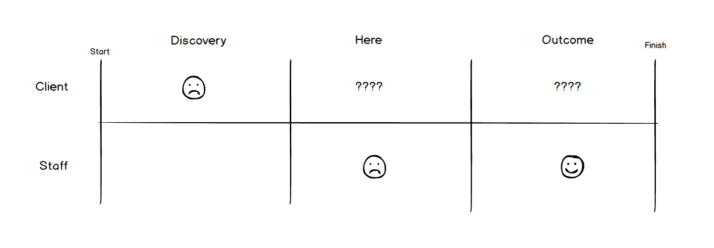

We structure stories as a journey with stages. Team members state what’s going on at each stage from a specific point of view—the client, staff, or end customer. In some parts of the journey we know a lot and in other areas we don’t. That’s OK. We can gather information later to fill in the gaps. By the time we are done, the team needs to arrive together to the conclusion that some areas of the journey need more attention than others. Below is chart showing a client’s journey as they discover a new service. Note that we describe their feelings as they move through the stages:

Ironically, the staff also have experiences during the journey and are not always feeling good along the way. Worst case, we don’t know how the client feels when they leave. Did they leave with a new insurance policy? Were their options salient to their characteristics and demographics? How long did it take them to complete the interaction? Did they have trouble finding offers in the first place?

Once the team talks through all of the problem areas, they get to vote. Everyone gets three stars or marks on a sticky-note:

Now we have identified a high-value business problem. Let’s work that problem into a specific statement.

Stating the Problem

The problem statement is the preamble to the remaining activities in this practice. There are many ways to phrase it. We follow the guidance from “Lean UX.” It goes something like this:

“Our service or product was design for these folks:

- Name your people/role (persona)

With these goals and capabilities:

- Goal 1

- Goal 2

We have observed that these goals are not being met in the following ways:

- Problem 1

- Problem 2

How might we measure improvement?”

The problem statement invites the team to engage in strategic thinking about what’s wrong with the world as it is. With this piece of work in hand we are ready to declare our assumptions about a solution.

Assumptions and Risk

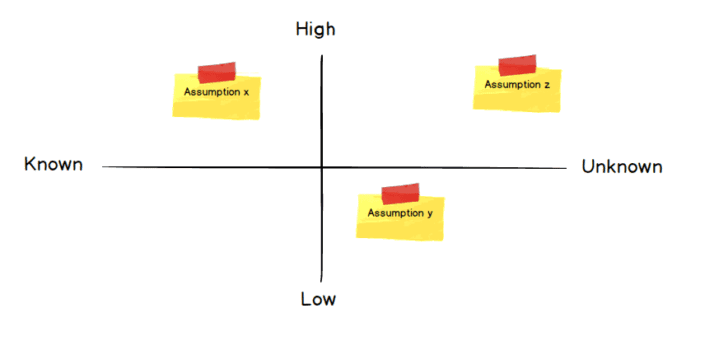

The assumptions portion of this workshop takes the most time with the team. We sit together with sharpies and sticky notes declaring all of the things we believe, based on a series of questions. These questions cover specific statements about the team, funding, go-to-market, users, making money, measuring, skills, timing, sponsorship, success, and failure. In the end, it’s not enough to state your end-game if capability or resources are not at hand. All of this risk needs mitigation through planning. It’s best just to get it out there and form some plan based on the biggest risks and assumptions that need to be proven true or false.

We set up a grid based on the “Lean UX” practice. Each team member comes forward and states their assumptions with a ranking against two dimensions: High-Low Risk and Known-Unknown Risk. By the time we are done, the team members have shared, removed duplicates and pondered over the categorized results.

Common known risks that I have seen include assumptions around people, timing and skills. In some cases these can be strengths as well. What can be hard to gauge are the intangible capabilities acquired during execution that never showed up on the risk board. In a project retrospective, folks might discover they had all the parts but were missing key capabilities in the areas of project management, forecasting and inter-departmental collaboration. I believe there will always be surprises. Let them unfold and improve your project as the challenges reveal themselves.

At this point, the team understands the breadth and scope of what needs to be done. More importantly, we know why the solution is important to the business. One more step makes the effort actionable. We need to state our approach as a new goal.

Stating the Goal

A good goal has three necessary parts:

Once you know your Who, What, When, you can formulate the goal like this:

We believe that our [people, role, client] will have a better experience doing [name the activity or journey] by making the activity: [improvement], [improvement], [improvement] within the next [timeframe]. We will accomplish this by doing [activity], [activity] and measuring progress with [metric], [metric].

A stated goal does not have to be perfect. Having all of the elements makes the greatest impact. In fact, just having the metric discussion changes the landscape for most organizations that don’t track project-level success for the business.

One criticism is the missing “why” from the problem statement. Zach Beer, one of my collaborators on this article, felt that its absence diminished the value of the goal. The “why” is the difference between believing and not. One suggestion is that you playback both your problem statement and goal together initially for buy-in. Together, they form a complete package.

Now, the business initiative is framed and packaged. Some readers may be wondering what this has to do with Decision Management. After all, where are the decisions in this work? Ultimately, decisions impact business goals and user experiences. If we don’t know what business transformation we are looking for, we will never know if our automation is helping or hurting. Timeframe and metrics help push decision management initiatives in the areas of rapid modeling and measuring outcomes. The rest just falls into place.

Let us know if you liked this article and are interested in us facilitating this workshop for your team. We call it our “Assumptions Workshop.”

(Thank you Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden for such an insightful text – LEAN UX, Designing Great Products)